The increase in safety standards and mitigating future risks

The 2010 Macondo oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico acted as a wake-up call for the subsea exploration industry and prompted the US administration to enact a series of reforms to improve safety across the sector. New procedures, rules and regulations were adopted beyond the confines of US waters and led to a decline in incidents throughout the following decade. However, 12 years on, a Center for American Progress (CAP) review has found that oil spills and injuries from offshore drilling are on the rise, threatening to erase the progress made over this period. In this article, we discuss the forces that drive increases in safety standards and why more still needs to be done to mitigate future risks and avoid another global tragedy.

Reflecting on the past

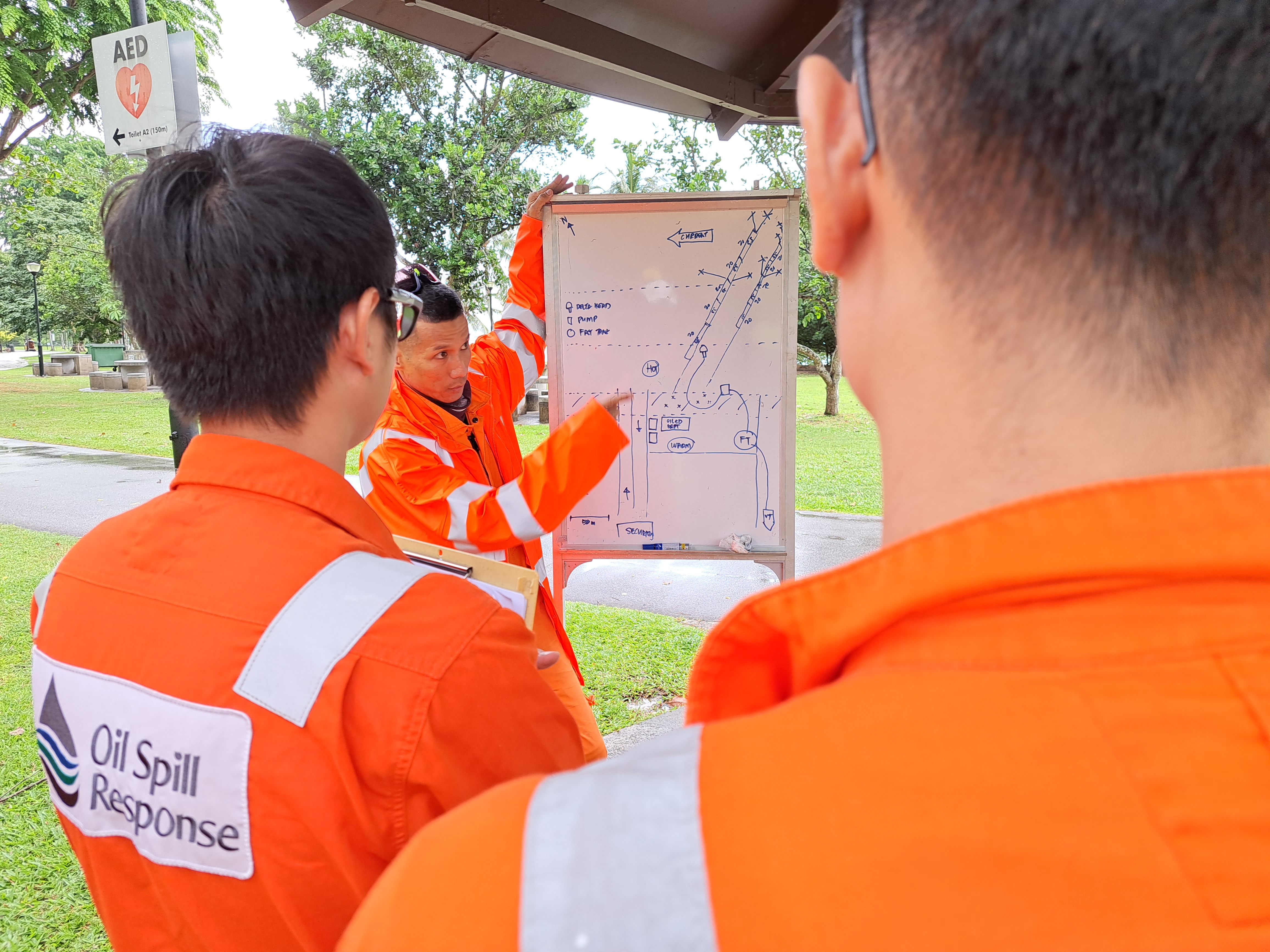

When we consider the drivers for increases in safety standards, we know our industry takes learnings from past events very seriously, and today develops rigorous systems to avoid history repeating itself and enable effective response mechanisms. However, if Macondo taught us anything, it’s that we can’t become complacent and responding to an incident is no substitute for ensuring it doesn’t happen in the first place.

If we look at data from the past five decades, we can see that the number of oil spills globally has declined significantly, particularly for major spills, which is why any change to this trajectory must be carefully analysed. Low probability doesn’t mean zero probability, and it is imperative that we do not return to a pre-Macondo mindset by focusing on testing systems against likely scenarios and avoiding worst case scenario planning.

Technological advancements throughout the 20th Century enabled the world to go higher, faster, further, deeper, and bigger than ever before. But pushing things to the limits also increases the level of risk, especially to the environment. Up until the 1980s, society largely accepted these risks and ignored increasing levels of air and water pollution. Governments and much of society took the view that it was the next generation’s problem – it was more important to maintain the low cost of energy, goods, and services. Today, many of us think differently, we see the world differently and, most critically, we know that we have a responsibility to protect the environment.

So why the change? Public and governmental attitudes to environmental protection have improved dramatically in the last 30 years. Whilst it is true that we are all far more educated on the potential ramifications of environmental disasters and businesses are more acutely aware of the potential for reputational damage, we’ve also learnt lessons the hard way. Better knowledge and understanding has, sadly, often come at the expense of human lives or the destruction of environmental habitats following avoidable accidents and disasters.

One would assume that health, safety and protection of the environment are now central to every business’ strategic goals. However, the reality within oil and gas exploration is that change driven by valuable and often painful lessons is not always as simple or consistent as some would expect. Complex analysis and years long investigations can result in multiple and sometimes competing recommendations. These outcomes could be voluntary or regulatory and could affect design, construction, or performance criteria. In some instances, the industry may be less willing to accept the advice or mandate due to it already being outdated, the poor understanding of the industry by the regulator or investigation body, the disproportionate financial implications of compliance or the likelihood of circumstances repeating being deemed to be negatable. Even more common is regulations being implemented on only a national basis, with other nations and businesses based in less developed regions unwilling or able to follow the lead of more proactive governments.

Looking Forward

Responding to previously realised risks is one thing and most organisations understand that there is no excuse for not putting procedures in place to refrain from repeating an avoidable scenario, but are we doing enough to predict how developments in our technology, operations or operating environment could lead to new risks? Are we exploring the risks we may face in the future? And if we are, how do we safeguard against events that have never happened?

We only have to look at the shipping industry to see how developments in vessel size, geo-political instability, changing weather patterns and the nature of the cargo all present emerging risks that are only starting to be considered.

The shipping industry already has a greater propensity for significant incidents than oil and gas exploration, as there are many more variables affecting risk, i.e., the cargo is more diverse, and the scale of operations is much larger. For example, in February this year, the 60,000 gt car carrier, Felicity Ace, caught fire and burned for over a week before recovery teams could board. While being towed to safety, the ship sunk and is now two miles beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. The vessel was carrying thousands of cars equipped with lithium-ion batteries, as well as thousands of gallons of oil and gas, posing a very real threat to the marine environment for years to come. The shipping industry recognises that there is still limited data concerning electric vehicles and their potential fire risk, which means the ship’s crews may not have the right tools or training to fight these fires. Should the nature of the cargo mean additional safety measures and changes in ship design are put in place?

Another emerging threat that is yet to be properly discussed is autonomous vessels. While there is no doubt that autonomous solutions are key to achieving shipping’s zero-emission ambitions, ensuring these vessels have the requisite safeguards on board to deal with challenges such as cyber security, or increasingly extreme weather conditions is paramount. Regulation is too often reactive so are we placing too much faith in the industry to put the environment first?

Standard P&I club warns that the frequency and ferocity of the storms are increasing year on year, causing much more damage and a greater risk of incidents. Are autonomous vessels able to respond to freak weather in the same way manned vessels are? Is the AI that is managing their transit developed enough to ensure environmental safety trumps operational performance or should they be regulated to guarantee this is the case?

The World Shipping Council’s 2022 report noted an ‘unusually high’ number of incidents, with estimates that an average of 3,113 containers were lost at sea in the two-year period of 2020-2021. The report takes into account significant events such as the One Apus stack collapse in December 2020 that resulted in the loss of more than 1,800 containers in one incident alone. In addition to the significant pollution hazard containers present through dangerous cargo and hazardous and noxious substances (HNS), they are themselves a navigation hazard and could cause an oil spill incident through a collision.

Incidents such as the grounding of ships pose significant risk and are often caused by human error, sometimes inadequate information related to the port or supply chain pressures, resulting in ships entering unfamiliar ports. Manoeuvring inattention and improper navigational operations should also be listed as common causes of major ship grounding accidents, which was the case in the recent Suez incident with the Evergreen vessel.

The vast majority of international oil companies (IOCs) have pledged to reduce their carbon footprint to zero by 2050. Meeting this target means a variety of approaches will be required, and this potentially includes pulling out of hydrocarbons completely or minimising future exploration projects. The US Energy Information Administration estimates that energy demand will increase 47% in the next 30 years so it can be argued that we will likely see an energy gap as the world struggles to match supply with demand. Smaller, independent oil companies are already acquiring assets being divested by IOCs. It’s normal that these smaller players, take on ageing infrastructure, but when taking on these assets they must recognise that each asset has a design life and need a greater degree of maintenance to ensure asset integrity and avoid a major incident.

Smaller oil companies may choose not to go beyond the legal minimums in terms of safety standards and not necessarily have deep enough pockets or the structures in place to deal with a major blowout effectively. In many countries, the government stipulates minimum insurance levels to allow for this, but this doesn’t necessarily occur everywhere.

Lastly, The current situation in Russia is a good example of where political instability can affect risk and further information can be found in our Thought Leadership article entitled ‘Russian Sanctions and the Laws of Unintended Consequences’.

Should We Use History to Predict The Future?

Should we use history to predict the future? We can apply the learnings from events and incidents, but we must not only rely on history. History explains the past and gives an understanding of what may occur in the future but does not necessarily give us the whole picture.

As outlined above, there are several potential risks, often interconnected which attribute to multiple accidents and incidents which no one should ignore. Recommendations to address lack of training, cost-cutting, and deviation from standard operating procedures due to delays or operational pressures are commonplace and designed to overcome the human factor in accident causation.

Ultimately, legislation is an effective method of enforcement but, on the international stage, this is notoriously slow so as not to disadvantage less-developed nations. Effective communication and dissemination of lessons learned will remain a challenge, particularly at industry, national and global levels. Corporate attitudes have improved and OSRL’s members are a demonstration of the commitment of the most environmentally conscious businesses, but we still have the opportunity to go further, to have more open, collaborative, and transparent conversations about how, as an industry, we can be more proactive, take the lead and ensure we are prepared for the future, whatever challenges it will bring.