Russian Sanctions and the Laws of Unintended Consequences

As the terrible events in Ukraine continue to play out, international operators such as BP, Shell, and Exxon have announced that they would exit from their Russian assets. Numerous governments have brought forward legislation to prevent imports of Russian oil and gas into their territories. In our latest insights article, Rob James explores the oil spill risk implications of Russian sanctions as countries seek alternative supplies and Russia looks to secure customers for its oil.

Going Cold-Turkey on Our Addiction to Russian Oil

As the terrible events in Ukraine continue to play out, international operators such as BP, Shell, and Exxon have announced that they would exit from their Russian assets. Numerous governments have brought forward legislation to prevent imports of Russian oil and gas into their territories. The USA has banned Russian oil imports with immediate effect, the UK by the end of 2022. However, neither the USA nor UK are heavily dependent on Russian oil and gas.

The European Union is a major market for Russian hydrocarbon exports. Across the 27 members, there is consensus that the EU should act. However, the extent and timing of that action remain a question with a spectrum of opinions across the members.

The President of the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said the EU must get "rid of our dependency on Russian fossil fuels,” aiming to reduce the use of Russian energy by two-thirds within a year and entirely by 2027. However, the EU is not likely to decide until May of this year.

The EU imports 70% to 85% of its Russian crude oil via tanker exports via the Baltic or Black Seas. The Druzbha pipeline provides the balance, supplying refineries in Poland, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, and Chechia (Source: Transport and Environment). In the last month for which data is available, November 2021, European Union countries imported almost 3mb/d of crude oil of which some 750kb/d came via the Druzbha pipeline. (Source: IEA)

If not from Russia, then from where (and how)?

If the EU is to reduce its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons or ban them altogether, even by 2027, it will need to secure alternative sources of crude oil supply.

Despite the multiple excellent and well-funded initiatives toward energy transition, these will not be in place within this brief time horizon. (Source: IEA) The most immediate source of the required replacement crude oil supply rests in the Middle East with OPEC members such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. Diplomatic efforts are in process on this front. (Source: BBC) If some rapprochement is reached with Iran, then they could also join this group.

If replacement capacity comes via this route, we will see additional tonnage transiting the Suez Canal and the SUMED pipeline. A 3mb/d gap in supply will take some 3,000 SuezMax tankers per annum to fill, without taking account of any return transits. Current transits through the Suez of all vessel types stand at just under 20,000 vessels of all types per annum. (Source: Suez Canal Authority)

Although such extra fleet capacity may not be immediately available, this would represent a significant increase in traffic. It may also open the potential for sub-standard vessels and crews to enter the market due to the demand for non-Russian oil. Tankers may then transit the Mediterranean, the Bay of Biscay, and the English Channel to reach ports such as Rotterdam or could be routed via the Adriatic Sea to Triste to feed the Transalpine pipeline supplying German, Austrian and Czech refineries. The Transalpine network transported some 750kb/d of Crude in 2021 (source: Transalpine Pipeline)so replacing the current Druzbha pipeline capacity If the EU is to reduce its dependence on Russian hydrocarbons or ban them altogether, even by 2027, it will need to secure alternative sources of crude oil supply.

Whilst refineries across Europe seek to replace Russian imports, Russian Exploration & Production companies will be looking for new export routes for their oil to locations that have not placed them under an embargo. Existing Russian crude export routes from Primorsk via the Baltic will become longer, passing through the English Channel and then onwards to a sanctions-free recipient. Similarly, Russian exports from Novorossiysk via the Black Sea will now have to continue through the Mediterranean either through the Suez or Straits of Gibraltar to their new destinations.

As an aside, we may speculate whether these vessels are likely to be inclined to meet the emissions limits set across various Emission Control Areas in the EU and elsewhere. The impact on SOx, NOx and particulate (PM10) emissions may be significant.

More Vessels Sailing More Miles Means More Risk

As Europe secures new sources of crude for its refineries and Russia seeks new markets for her crude exports, we can expect significant extra tanker traffic in both directions through the Suez, the Mediterranean, the Straits of Gibraltar, the Bay of Biscay, and the English Channel. We know that Risk = Frequency x Probability and with these increased tanker mileages through a series of pinch-points the “frequency” side of the equation certainly increases.

The “probability” side of the equation may also rise, especially if Russian flagged vessels sit outside the International Classification Societies on a purely Russian Register with insurance cover also moving to local, Russian, providers. (Source: Lloyds List) Sanction-busting vessels also have a history of turning off their AIS (Automatic Identification System) transponders to avoid detection, increasing the risk of collision, engaging in night-time ship-to-ship transfer operations to disguise cargoes, and other risky practices.

Regardless of sanctions, if a Russian-flagged vessel, carrying Russian crude is involved in an incident, say, in the English Channel, the oil spill impact (and potentially clean-up costs) will present itself in the local littoral states (in this case France and the United Kingdom).

Post the Macondo oil spill, some may view oil spill risk as an issue for the Exploration & Production sector only, as shipping risk is inherently lower due to smaller hydrocarbon inventories and robust vetting and ship management procedures. However, given the current situation, it may be time for oil producers, states along shipping routes, ship owners, and P&I Clubs to re-visit their assessment of shipping risks as their risk will increase with increasing vessel movements.

Gas Supply – A Different Ball Game

The challenge to replace Russian crude oil imports is one thing, but the replacement of Russian gas presents a whole new challenge. Many European countries rely heavily on receiving Russian gas exports via pipeline to meet their domestic needs. Replacement of this gas would come primarily via imports of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) by vessel from producers worldwide.

In 2021 the European Union imported 155 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia. (Source: IEA) Whilst governments can take many actions to reduce the overall requirement for Natural Gas if LNG is to be the like-for-like replacement of this demand, then some 1,000,000 deliveries (assuming an average LNG vessel capacity of 150,000 m3) by LNG vessels would be required into EU facilities!

Practically, such a level of cargo is highly unlikely to transpire, and certainly not in the near term as the global LNG carrier fleet only stood at 642 vessels at the end of 2020. (Source: Statistica)

A recent IEA (International Energy Agency) publication proposed several ways to reduce gas consumption in the EU but still concluded that some 30 billion cubic metres per year would have to come from alternative imports, even after the EU implements a raft of long-term energy transition actions. (Source: IEA)

Regardless of the speculative mathematics, it is a reasonable assumption that there will be significantly more vessel trips from locations such as the Middle East, West Africa, and the USA to the EU than there are currently.

We can also safely assume that the LNG fleet will increase and that any given LNG vessel will be carrying out as many sailings as possible. As with crude oil tanker miles, as Risk = Frequency x Probability, then with these increased LNG carrier mileages through a series of pinch-points, the “frequency” side of the equation certainly increases.

If an LNG carrier is involved in an incident, then there may be a need for an emergency lightering operation to transfer the LNG cargo to another vessel.

We Have Time To Prepare – Let’s Use It

Organisations across the shipping sector and countries with exposure to shipping risk should start their preparations to reduce the risks identified here and ensure that the consequences of any incident will be well-mitigated. Some actions for all concerned to consider are listed below:

- Places of Refuge are still an unresolved issue where the international community needs to redouble its efforts.

- More focus and funding for relevant UNEP (UN Environment Programme) Regional Clean Seas initiatives for bodies of water along these potentially crowded shipping routes, such as ROPME (Regional Organisation for the Protection of the Marine Environment) (Regional Organisation for the Protection of the Marine Environment)- MEMAC (Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre), PERSGA, NOWPAP, and HELCOM will also help.

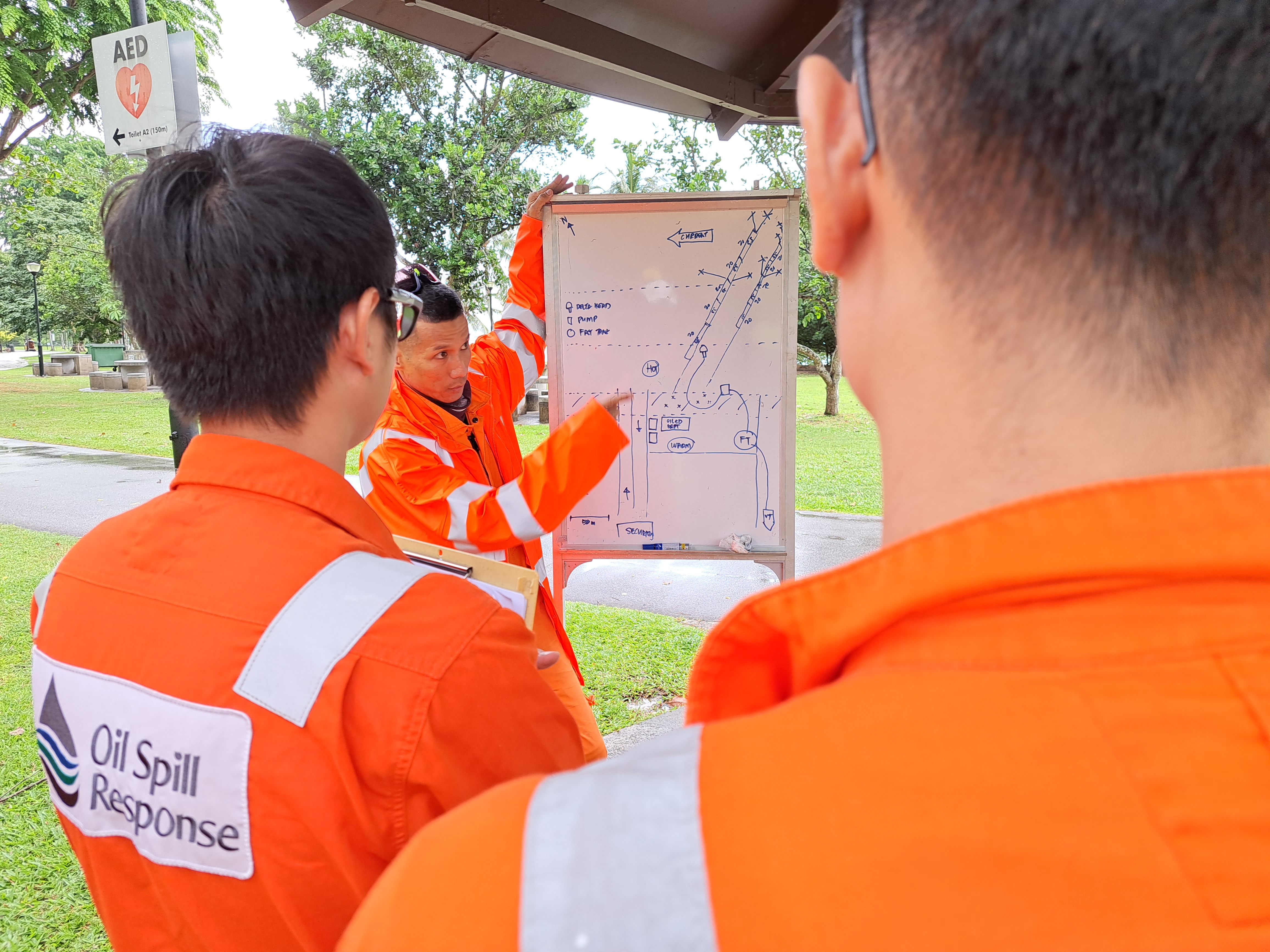

- Oil companies who have interests in cargo on these routes, especially those with captive shipping lines, should review their Oil Spill Contingency Plans, ensure that those plans are exercised regularly, and train more personnel to deliver those response plans.

- P&I Clubs should review their risk exposure and consider how they can reduce risks and minimize clean-up costs. Clubs may also consider incentivising well-prepared operators through reduced premiums; assurance specialists could validate contingency plans and overall levels of preparedness.

- LNG cargo owners and vessel operators should consider the status of their Emergency LNG Ship-to-Ship transfer arrangements or what should be and ensure that the plans, resources, and training are in place to deliver these highly specialised services.

We hope and pray that a speedy and peaceful resolution is found to the war in Ukraine with no further loss of life. In the meantime, though, as we see the potential for major changes in oil and gas supply routes, then oil spill professionals must as ever, be prepared.